San Jose Mercury News | September 14, 2016

Ever since their two children were diagnosed with autism, San Jose mother Renee Trevino and her husband, Michael, have done whatever it takes to help Isaiah, 7, and Ava, 4, function at higher levels.

So when Kaiser Permanente researchers asked the family if they would submit a blood or saliva test for a study surrounding the cause and new treatments for autism spectrum disorder, the Trevinos were more than willing to oblige.

“If we can do anything to help to understand why our kids are going through this, I am happy to do everything we can,” said Renee.

The Trevinos are one of 1,200 families helping Kaiser Permanente’s Northern California Division of Research build the Autism Family Biobank that the health care giant set up last summer for its Northern California member families with autistic children.

To sign up, eligible Northern California Kaiser families can sign up at autismfamilybiobank.kp.org, contact autism.research@kp.org or call 866-279-0733 for more information.

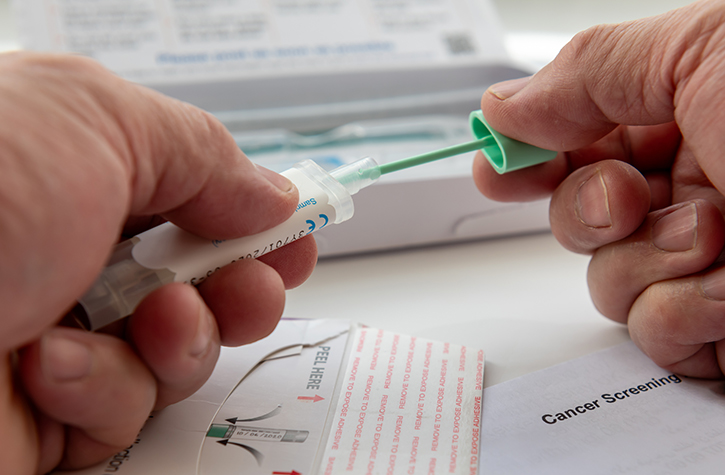

Through samples of saliva or blood, Kaiser researchers are collecting the genetic material of each child and his or her biological parents, as well as medical and environmental information for all three members of the family.

But to reach their goal of 5,000 families, the researchers need 3,800 more such “trios” to sign up by 2018, when the deadline — and a $4.6 million grant — runs out.

“How could you not want to do this?” asked Kaiser member and Oakland resident Tiffany Van Buren, whose 7-year-old daughter, Devyn, is autistic. “It was so simple!”

Autism is a relatively common neurodevelopmental disorder — defined by impairments in social interaction and communication, and restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior — that occurs in 1 in 68 children, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Yet when it comes to participating in autism studies, many families still balk, saying they don’t have time, while others are anxious about their privacy. Even a handful of Trevino’s relatives and friends were wary of her getting involved with the study.

The New York City-based Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative is funding the project; ultimately, the data will be made available to researchers worldwide, though cleared of any identifying information.

Trevino understands why some families might worry about that aspect.

“I think that’s pretty normal — people who want to keep their privacy don’t want to have these samples all over the place,” said the mother. “And they don’t know what’s being done with them.”

The reluctance of some families to engage in such research might baffle outsiders — after all, the point of the research is to help their own children with autism. But these bumps in the road aren’t new to Lisa Croen, director of the Kaiser Permanente Autism Research Program.

Yet they can be frustrating.

“Right now, we have a 25 percent refusal rate — but that does not mean 75 percent have said yes,” said Croen. “About 50 percent are still unknown — we have not closed them out. But we would like the numbers to be much higher in terms of people saying yes.”

Among a plethora of autism studies that have been launched in the U.S., this one is believed to be the largest in the country linked to electronic medical records, said Kaiser Permanente spokeswoman Janet Byron.

Key to Kaiser’s Autism Family Biobank is that it’s made up of only Northern California Kaiser member families, which Croen said offers multiple benefits not only involving their genetic information, but environmental influences that may be unique to the area.

“Not just toxins,” Croen explained, “but information about their lifestyle, nutrition, chemical exposure, illnesses and so on.”

And because Kaiser already has the families’ permission to review their electronic health records, Croen’s team can easily access their medical histories instead of having to obtain permission from individual health plans, a complication other researchers may face.

Of Kaiser’s 3.9 million members in Northern California — which includes the Bay Area counties, Fresno and the Central Valley, as well as Sacramento Valley — there are about 21,000 member families who have an autistic child, about 17,000 of whom likely meet the criteria for eligibility: a Kaiser Permanente member of any age with autism, and both their biological parents.

Croen said she needs only 5,000 families to ensure the right amount of participants.

“A more robust number allows you to subdivide the population being studied into groups that might have different risk factors for a type of autism, or manifestations of autism,” said the senior research scientist.

The veteran researcher said her 10-member team did not expect to collect the data needed from 5,000 families all at once.

“You don’t send a letter out to 17,000 families,” said Croen. “You could not follow up with all of them.”

Rather, she said, the team anticipated that the monthly numbers would gradually increase as the team continues to reach out to more families. And while she said they are on track to hit 5,000 families, public reminders never hurt.

“It’s a challenging job to raise children, especially if you have a special needs kid,” said Louis Reichardt, director of the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative, of the painstaking process of attracting participants to clinical study.

“Families are undergoing a lot of change and turmoil. School school starts and ends. Some parents don’t want to put their children through blood or saliva samples,” said Reichardt, a former UC San Francisco professor of cell physiology who directed that school’s renowned neuroscience graduate program for 25 years before joining Simons in 2013.

Other parents aren’t interested, or they may live somewhere else.

“There is every reason under the sun” not to participate, he said.

Letters are sent to families via postal and email asking them to sign up for the study. The research team then follows up with a phone call or email to find out if they’re interested in participating and which sample they would prefer to donate. But Croen said it’s not necessary to wait for the initial letter; families can contact the Division of Research’s Autism Family Program or visit its website for more information.

The parents also are asked to fill out two brief surveys.

Though the Trevinos chose the blood test, most families, by 4 to 1, are submitting saliva samples, said Croen.

“We prefer blood because there are more things you can measure in blood, aside from genetics,” said Croen. But saliva works just fine, too — and it’s easier for most families.

“Whatever we get is extremely useful,” she said. “As technology advances and science progresses, there will be more and more things we will be able to measure from saliva samples other than DNA.”

Van Buren said that she, Devyn and Devyn’s father, Sean Handran, opted for the saliva test, sent to them in the mail. The family even had some fun with the test, competing to see who could produce the most spit in one shot into a container.

Compared to past autism-related studies Kaiser researchers have asked her to participate in — including one a few years ago that required several hours of testing over a couple of days — “this was super easy,” said Van Buren. So there is no excuse, in her mind, not to sign up.

“If you want medical answers,” she said, “then you need to be willing to participate in the research to provide you with those answers.”

TO SIGN UP

Eligible Northern California Kaiser families can sign up at autismfamilybiobank.kp.org, contact autism.research@kp.org or call 866-279-0733 for more information.

This article appeared in the San Jose Mercury News on September 14, 2016