July 23, 2020

The number of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer in Kaiser Permanente Northern California during the first 12 weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic was more than one-third lower than what would be expected, a new Kaiser Permanente study found.

The research paper, one of the first to look at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer detection, was published online July 23 in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

“We expected screen-detected cancers like breast cancer would decrease because of the pandemic,” said lead author Betty Suh-Burgmann, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at The Permanente Medical Group and a physician researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. “But we didn’t know what would happen with other cancers. When my colleagues and I saw a drop in referrals for endometrial cancer to our practice, I decided to study the issue more formally.”

“We expected screen-detected cancers like breast cancer would decrease because of the pandemic,” said lead author Betty Suh-Burgmann, MD, a gynecologic oncologist at The Permanente Medical Group and a physician researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. “But we didn’t know what would happen with other cancers. When my colleagues and I saw a drop in referrals for endometrial cancer to our practice, I decided to study the issue more formally.”

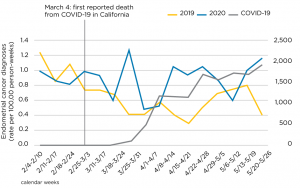

Dr. Suh-Burgmann and her team reviewed electronic medical records to determine the number of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer in Kaiser Permanente Northern California in the 12 weeks following the first death from COVID-19 in California on March 4, compared with the same 12-week period in 2019. They found that 191 patients were diagnosed with endometrial cancer from March 4 through May 26, 2019. During those 12 weeks in 2020, the number of diagnoses dropped to 127 — a 35% decline.

To tease out the reason for the decrease, the research team also investigated the weekly rate of calls to the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Appointment and Advice Call Center related to abnormal vaginal bleeding during the same 12 weeks in 2019 and 2020. They found that in 2020 the number of calls decreased by 33%, nearly the same amount as the number of diagnoses. However, the study also showed that during those 12 weeks the proportion of cancer diagnoses that were preceded by a call to the center for bleeding was about the same. “This suggests the reason we diagnosed fewer endometrial cancers was not because we weren’t following up calls with a biopsy when indicated, but because people were not complaining of symptoms, likely due to fear of COVID-19,” Dr. Suh-Burgmann said.

The postponement of routine screening visits and the shift to virtual appointments that began during the pandemic may have also created fewer opportunities for incidental diagnoses to occur. “Incidental detection can occur in someone who comes in for an unrelated health issue and in the course of the visit says, ‘oh, by the way, I also have some bleeding’ — or the doctor happens to ask about bleeding — which leads to the biopsy and the diagnosis,” Dr. Suh-Burgmann said. “This may be less likely to occur in a virtual visit.”

Endometrial, or uterine, cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in the U.S. The American Cancer Society estimates that this year about 65,000 people will be diagnosed with endometrial cancer and about 12,500 people will die from the disease. There is no screening test for endometrial cancer. It is most commonly detected by biopsy after a patient tells their doctor they have had abnormal vaginal bleeding.

Dr. Suh-Burgmann said she is now starting to see some of the patients who didn’t call when they first started to have symptoms. “I now have patients saying to me, ‘I started to have bleeding 3 or 4 months ago, but I was so scared about COVID I didn’t want to come in.’ Now, since the bleeding has gotten worse, they decided it was time to make an appointment.”

About 80% of endometrial cancers are slow growing. For patients with these cancers, a delayed diagnosis of 3 to 4 months is unlikely to affect their outcomes. But for the 20% of patients with a high-grade, aggressive endometrial cancer, “a delay of 3 to 4 months could alter the stage of their diagnosis,” Dr. Suh-Burgmann said. “And, of course, you don’t know the grade until you do a biopsy.”

Dr. Suh-Burgmann wants patients to be aware that if they are having any abnormal bleeding, they should not delay making an appointment to see their doctor. “Based on the numbers we saw in our study, we know that there are people out there who have endometrial cancer but remain undiagnosed.”

The study was funded by The Permanente Medical Group Physician Researcher Program.

Co-authors include Mubarika Alavi, MS, and Julie Schmittdiel, PhD, of the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research.

This story originally appeared in Divison of Research Spotlight