May 23, 2022

Culturally tailored lifestyle coaching can help Black adults with hypertension improve their blood pressure control, new Kaiser Permanente Northern California research shows.

Stephen Sidney, MD, MPH

“Black adults have the highest rates of high blood pressure and, for reasons we don’t fully understand, it starts at a younger age and results in strokes, heart attacks, heart failure, chronic kidney disease, and other serious hypertension-related health problems occurring at an earlier age as well,” said senior author Stephen Sidney, MD, MPH, a research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. “We know how to treat high blood pressure with medication, but there is also a huge role that behavior change can play in prevention and treatment. This study was a tremendous opportunity to see if we had an intervention that could change behaviors and get blood pressure under control.”

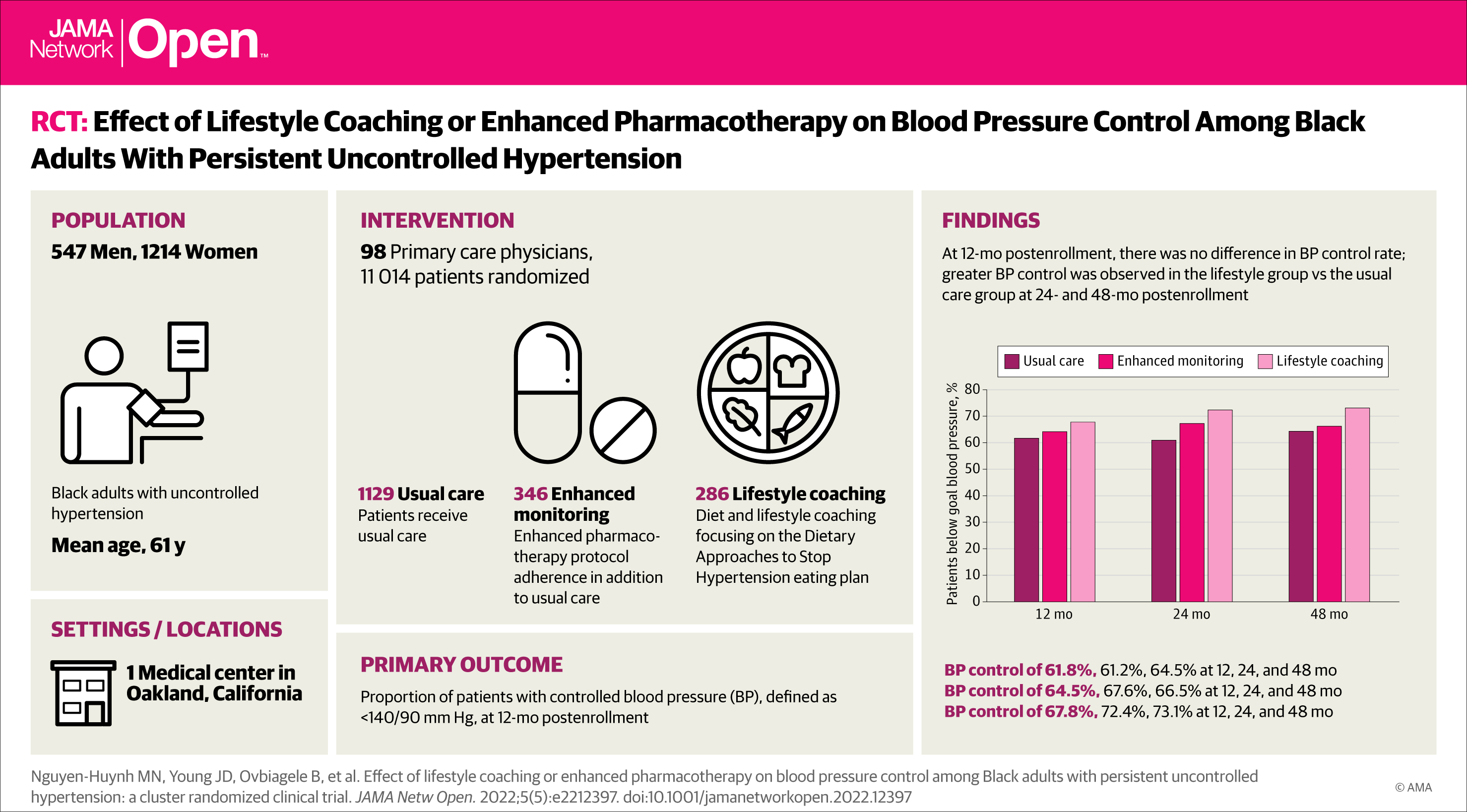

The study, published May 18 in JAMA Network Open, included 1,761 Black adults with high blood pressure who were members of Kaiser Permanente Northern California. The patients joined 1 of 3 groups: usual care; enhanced medication management and usual care; or lifestyle phone coaching and usual care. Then, the researchers analyzed the impact the programs had on blood pressure control at 12, 24, and 48 months post-enrollment.

Statistical analyses showed no significant difference in blood pressure control among the 3 groups after 12 months. However, at both the 24-month and the 48-month mark, blood pressure control was significantly better among the patients who had received the lifestyle coaching than it was among those in the enhanced medication management program or the usual care only group.

At 24 months post-enrollment, 72.4% of the patients who received lifestyle coaching had controlled blood pressure, compared with 67.6% of the patients in the enhanced medication management program and 61.2% of patients receiving usual care. At 48 months the differences were sustained, with 73.1% of the patients in the lifestyle coaching group showing controlled blood pressure compared with 66.5% of the patients in the enhanced medication management program and 64.5% of the patients receiving usual care.

Mai N. Nguyen-Huynh, MD

“We had hoped that a 12-month coaching program could help people learn how to start a healthy, low-salt eating plan,” said lead author Mai N. Nguyen-Huynh, MD, MAS, a research scientist at the Division of Research and the Kaiser Permanente Northern California regional medical director for primary stroke for The Permanente Medical Group. “But what was really eye-opening was learning that after the 1-year program ended these patients continued to have better blood pressure control, perhaps by sticking with the lifestyle changes they had learned — even though we had no contact with them.”

In the lifestyle intervention group, 286 Black adults with high blood pressure took part in up to 16 phone coaching sessions with a registered dietitian who talked to them about their diet choices and helped them lower their salt intake by adhering to the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) eating plan. The 346 Black patients enrolled in the enhanced medication management program met with a research nurse or a clinical pharmacist to discuss the importance of blood pressure control and the importance of taking their medication. When appropriate, patients in this group were also prescribed the drug spironolactone to further help control their blood pressure. The third group of 1,129 Black patients received routine care provided by KPNC primary care providers to patients with high blood pressure.

Black adults have significantly higher rates of high blood pressure than white, Latino, and Asian adults, and lower rates of blood pressure control. The new study was funded through a national effort aimed at developing programs that can reduce stroke disparities in minority communities.

The researchers said they believe their findings could lead to the introduction of similar programs that can help Black adults learn about dietary changes that improve blood pressure control. “This research opens up the door for the creation of programs that could be offered on a larger scale that implement the principles of coaching for behavioral change that we have shown can be effective,” said Dr. Sidney.

The researchers said they believe their findings could lead to the introduction of similar programs that can help Black adults learn about dietary changes that improve blood pressure control. “This research opens up the door for the creation of programs that could be offered on a larger scale that implement the principles of coaching for behavioral change that we have shown can be effective,” said Dr. Sidney.

Added Dr. Nguyen-Huynh: “This is the only trial that has shown that a lifestyle coaching intervention can bring about changes that lead to better blood pressure control long after the intervention has ended. We’ve learned from the participants’ feedback what they felt were the most helpful aspects of the program, and we can use them to guide our next steps.”

The study was funded by The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) Stroke Prevention/Intervention Research Program (SPIRP).

Co-authors include Janet G. Alexander, MSPH, Stacey Alexeeff, PhD, Catherine Lee, PhD, Noelle Blick, MPH, Bette J. Caan, DrPH, Alan S. Go, MD, of the Division of Research; Joseph D. Young, MD, of The Permanente Medical Group; and Bruce Ovbiagele, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco.

This article originally appeared in Division of Research Spotlight.