September 20, 2022

Boys and girls who develop obesity at a young age are more likely than children with a normal, or healthy, weight to start puberty earlier, new Kaiser Permanente Northern California research shows.

The study, published August 23 in the American Journal of Epidemiology, is one of the first to study a large racially and ethnically diverse group of boys and girls from age 5 to 6 through puberty. The findings highlight the ongoing need to address the socioeconomic inequalities that increase risk for childhood obesity in the U.S.

Ai Kubo, MPH, PhD

“Childhood obesity has been known to be a risk factor for early puberty in girls, but this is the first large population-based study to show this relationship in boys,” said the study’s senior author Ai Kubo, PhD, MPH, a cancer epidemiologist and research scientist at the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Division of Research. “This is significant because we know that in adolescents early puberty is tied to an increased risk for depression and other mental health and behavioral problems. In adults, early puberty is a cancer risk factor, and it’s also been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease and diabetes.”

The new study included 129,824 racially and ethnically diverse boys and girls born at a Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) hospital between 2003 and 2011 and followed through 2021. The research team reviewed electronic medical record data to determine each child’s weight and height at age 5 to 6 and then the age they started puberty. Physicians routinely record in children’s medical records signs of sexual maturity — testicular size, growth of pubic hair, breast development, and start of menstruation — which allowed the researchers to determine puberty onset.

The researchers found that at age 5 to 6, 3.6% of the girls were underweight, 14.9% were overweight, 9.3% were obese, and 2.6% were severely obese. Those with severe obesity had a 63% greater risk of showing earlier breast development and an 88% higher risk of earlier pubic hair development than girls with a normal, or healthy, weight. The start of menstruation was even more closely tied to weight. Girls with severe obesity were 2.6 times more likely and girls with obesity were 2.2 times more likely to have their periods start before the age of 12 than girls with normal, or healthy, weight.

Among boys ages 5 to 6, 3.9% were underweight, 14.3% were overweight, 10.6% were obese, and 3.2% were severely obese. The study showed that the boys with overweight or obesity had a greater risk of experiencing earlier testicular development than the boys who had a normal, or healthy, weight, with the risk ranging from 23% higher for boys with severe obesity to 15% higher for boys who were overweight. Similarly, the boys with severe obesity had a 44% higher risk of showing pubic hair growth earlier than the boys with a normal, or healthy, weight.

“Our finding that boys have a similar relationship with obesity to puberty contradicts some other smaller studies that showed obesity is protective against early puberty in boys,” said Kubo. “This is important because we had a large enough group of boys to have a category of extreme obesity, and we were able to look at obesity in a very granular way and to see a clear dose-response relationship between weight and puberty onset.”

The study also found racial and ethnic variations in weight and signs of sexual maturity. For example, white boys with severe obesity showed signs of pubic hair about 7 months earlier than boys with normal, or healthy, weight, whereas Black boys with obesity showed signs of pubic hair about 6 months earlier. Among girls with severe obesity, Black girls showed signs of pubic hair about 12 months earlier; Asian Pacific Islander girls about 11 months earlier; and white girls about 8 months earlier than normal, or healthy, weight girls. The study also showed that white and Asian and Pacific Islander girls with severe obesity were 3 times more likely to start menstruation before age 12 than normal, or healthy, weight girls, while there was little association seen between childhood weight and age of menstruation in Black girls. The researchers said these differences are likely related to socioeconomic and psychosocial factors rather than genetic factors.

Louise Greenspan, MD

“Our study adds to the evidence that obesity is a marker of an environment that can lead to metabolic changes in kids,” said study co-author Louise Greenspan, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist with The Permanente Medical Group. “We don’t know that obesity is directly causing the early puberty, but we do know that both obesity and early puberty can lead to a lifetime of higher health risks.”

Certain intergenerational factors may also be contributing to both early obesity and early puberty, said Kubo. “There are exposures that children may have in utero that contribute to their increased risk for both obesity and early puberty,” she said. “These could include the mother’s diet during pregnancy, prenatal depression, or stress. It is important for clinicians to be aware that what happens in pregnancy can affect a child’s development and that we learn how to intervene to help the moms before their kids are born.”

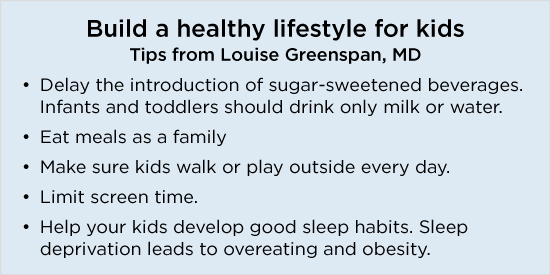

Dr. Greenspan said it is important that parents of children with overweight or obesity recognize that a child’s weight at puberty does not dictate their future health. “The children in our studies have only lived about 10% of their lives,” she said. “They have the whole rest of their lives to start building the habits that help keep them healthy.

“Most importantly,” she added, “we need to destigmatize and really change the conversation around overweight and obesity. They are medical conditions, not a personal deficit or a weakness. We also need to look at kids as part of a big system — and that system is broken. It’s not the parents’ fault.”

“Most importantly,” she added, “we need to destigmatize and really change the conversation around overweight and obesity. They are medical conditions, not a personal deficit or a weakness. We also need to look at kids as part of a big system — and that system is broken. It’s not the parents’ fault.”

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Co-authors include Sara Aghaee, MPH, Charles P. Quesenberry Jr., PhD, and Lawrence H. Kushi, ScD, of the Division of Research and Julianna Deardorff, PhD, of the University of California, Berkeley.

This article originally appeared in Division of Research Spotlight.