June 23, 2023

An innovative, multidisciplinary group of primary care physicians, ophthalmologists, optometrists, and quality and support teams are increasing equity and access to retinopathy screening for patients with diabetes.

A troubling memory of one of his earliest patients continues to drive Dr. Erold Jean-François to get more patients with diabetes to have their eyes checked.

“During my first year of residency in Los Angeles, a middle-aged woman with diabetes came to my clinic with acute, painless vision loss,” recalls Dr. Jean-François, chief of ophthalmology at Kaiser Permanente (KP) Stockton Medical Offices and regional clinical lead of the Diabetic Retinopathy Screening program in The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG). “She was diagnosed with proliferative diabetic retinopathy and had extensive bleeding inside her eyes. Despite heroic efforts by our retina surgeons, she permanently lost vision in one eye.”

Diabetic retinopathy is the leading cause of blindness among working-age adults in the United States. The condition affects nearly 8 million Americans, and that number is expected to double by 2050. Yet many people with diabetic retinopathy are unaware that they have this preventable, sight-threatening disease. Screening rates for diabetic retinopathy range between 50% and 70% nationally — not nearly the rate they need to be.

A number of reasons explain why: Many people in general lack knowledge about diabetic retinopathy and the importance of preventive eye care. Racial, ethnic, and/or low socioeconomic status are associated with decreased utilization of eye examinations and decreased access to eye care. And patients with diabetes sometimes are so burdened by other aspects of their medical care that they skip these important eye screenings.

When Dr. Jean-François joined TPMG in 2011, he found a medical group already well on its way to redesigning care to address these issues. And by 2015, adult and family medicine physicians, ophthalmologists, optometrists, and quality care professionals had banded together to develop and implement a more coordinated approach that would increase access to retinopathy screening for patients when they are accessing routine primary care.

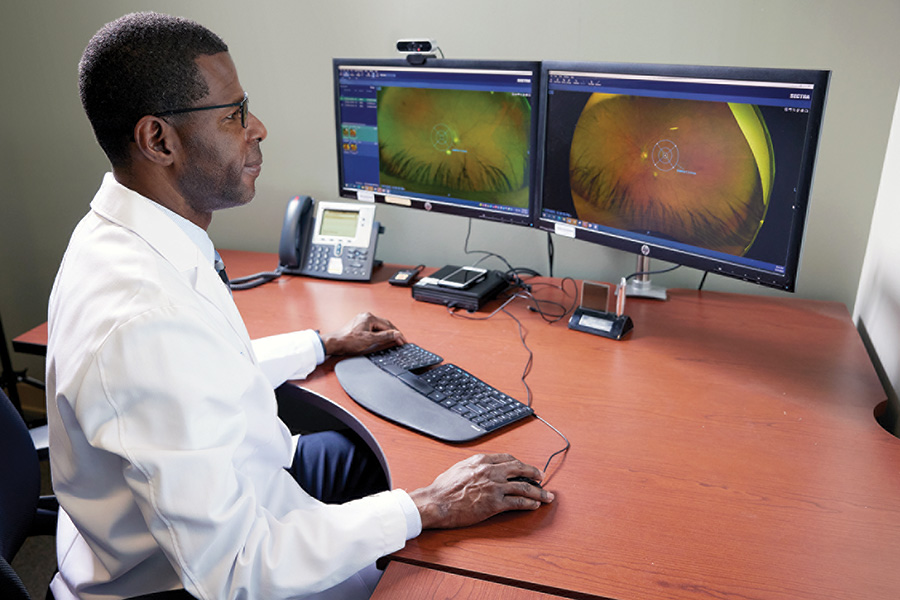

TPMG medical assistants, along with TPMG vision service assistants, have been trained over the last several years to capture images of the retina during routine office visits. The images are now digitally routed to a centralized eye-care monitoring system, where optometrists at any location in the KP Northern California region can screen them for signs of retinopathy.

Yi-Fen Irene Chen, MD

As a result of this redesign, the retinopathy screening rate for patients with diabetes is now 80% regionwide, which is above pre-pandemic levels. The National Committee for Quality Assurance placed KP Northern California in the top 10 in the nation in 2022 for diabetic eye screening of commercial members.

“We took a performance improvement framework, developed a patient-centered workflow, and collaborated with different departments to achieve this great outcome,” says Yi-Fen Irene Chen, MD, TPMG associate executive director. “Today we routinely diagnose many patients with retinopathy before they develop sight-threatening complications, and they tend to have better outcomes and earlier treatments, such as laser therapy or injections, that are less invasive than surgery.”

A major public health issue

When diabetes deprives the eye of the energy it needs to function properly, retinal ischemia and macular edema often develop and eventually cause visual impairment, Dr. Jean-François explains. As the disease advances, referred to as proliferative retinopathy, abnormal blood vessels that have grown on the surface of the retina break and bleed into the vitreous gel.

“The problem with diabetic retinopathy is that many patients are asymptomatic until they experience sudden loss of vision from bleeding inside their eyes,” says Dr. Jean-François. “Other patients might see some gray blotches in their field of vision, at which point retinopathy may already be severe.” But when the disease is caught early during routine screening, treatment can reduce the incidence of vision loss by nearly 95%.

“Lifestyle modifications such as healthy eating, regular physical activity, weight and blood pressure control, and smoking cessation, along with proper treatments to bring diabetes under control, are essential in reducing the rate of diabetic retinopathy progression,” Dr. Jean-François explains.

Patients with macular edema or proliferative diabetic retinopathy can be treated with intravitreal injections and/or laser therapies. These treatments help dissipate intraretinal fluid by decreasing vascular endothelial growth factor production.

Before the advent of easy-to-use retinal cameras, screenings were done with an annual dilated eye exam. This model of care created problems over time. For one, patients with diabetes often needed to take a half-day off from work and come into eye care services for a dilated exam every year, something that wasn’t always easy for them to do. Even after the care redesign in 2015, the TPMG Diabetic Retinopathy Screening team noticed that screening rates decline precipitously if patients need to go to a different floor or building to be screened.

“Unfortunately, many patients do not go to eye departments for screening, and one of the major barriers is simple convenience,” Dr. Jean-François says. “If a patient has to walk to a building next door for a screening, for example, we’ve found that the likelihood that they get screened decreases three- to five-fold. When those opportunities are missed, it takes many more interventions to get the patient back into the medical center for the screening.”

Robin Vora, MD

Another barrier has been the dramatic increase in diabetes diagnoses, which has impacted health care systems throughout the country — including KP Northern California. “The demand for diabetic eye screening has skyrocketed in the past decade,” says Robin Vora, MD, who is the TPMG co-chair of ophthalmology alongside Poorab Sangani, MD, and chief of ophthalmology at KP Oakland and Richmond medical centers. “Each time someone is diagnosed with diabetes, they need to be screened. We had to determine how we were going to quickly increase supply.”

A coordinated, joint effort

When TPMG launched the quality-improvement program for diabetic retinopathy screening, “the goal was the creation of a well-oiled machine,” says Smita Rouillard, MD, TPMG associate executive director. “The gears of the machine include messages in PROMPT, alignment of family medicine and ophthalmology, new cameras on hand at all times and distributed across the region with staff trained to use them, targeted patient outreach and inreach, and the virtual reading center for retinal images.”

Based on evidence in the medical literature, the team defined screening parameters, launched a “fast pass” for people with diabetes to be bumped to the head of the line for screening at the nearest eye department, and developed and distributed a playbook of best practices.

Erold Jean-François, MD

“The playbook includes recommendations for strengthening screening infrastructure and improving access to retinal cameras across the region, developing the right levels of staffing trained to use them, and coordinating follow-up treatment care for those at high risk of vision loss,” Dr. Jean-François says.

The redesigned model of care for retinopathy screening works like this: When members are initially diagnosed with diabetes, PROMPT displays a “needs photo” message in the patient’s electronic health record. This alerts medical assistants in adult and family medicine and vision service assistants in KP eye departments — many of whom have been trained to take photos with the retinal cameras — that a baseline screen is needed.

“Rather than having to make an extra trip to their local medical center, patients simply get the screenings done during a routine visit — it takes just 5 to 10 minutes of their time,” says Dr. Chen. “If we tell patients to go next door, we might lose them, but if we can do the screening on the spot, it’s much better for everyone.”

A centralized system for routing images

Once images are captured, they are routed to the virtual Eye Care Monitoring program for reading. Dr. Vora compares the program to a central shipping warehouse in which “numerous boxes enter the system and then are expertly guided through the network to the correct final destination.”

“Thousands of photos are taken across KP Northern California within eye care and primary care,” he explains. “Patients with normal results are routed to one destination, while those with more than minimal disease are routed elsewhere. Those with vision-threatening findings are routed to a special place so that they can get urgent care.”

More specifically, if optometrists detect no retinopathy in the initial image, the patient’s electronic health record is flagged for rescreening in ophthalmology, optometry, or their primary care physician’s office every other year. Patients who are found to have mild retinopathy are also flagged to be screened, but yearly rather than biennially. Cases of moderate-to-severe retinopathy, proliferative retinopathy, or macular edema are more closely managed by the patient’s ophthalmologist or retina specialist.

To get a sense of the volume of screenings needed, nearly 400,000 KP Northern California patients with diabetes need to have their eyes checked routinely for retinopathy. Of those screened each year, approximately have mild-to-moderate retinopathy, putting them at higher risk for vision loss, and about 5% have severe or proliferative retinopathy or macular edema, which puts them at significant risk of vision loss or impairment.

Reaching in and out to boost patient compliance

To support patients at risk of permanent vision loss from diabetic retinopathy, regional and local teams undertake targeted inreach and outreach. Member outreach includes sending secure messages, mailing letters, and calling patients whose screenings are past due, reminding them to self-book an appointment via My Doctor Online or the Appointment and Advice Call Center. Last year, for example, regional teams sent out approximately 400,000 outreach communications on behalf of primary care physicians.

Inreach is targeted to patients who are already at a KP facility for an in-person office visit. If the patient is due or overdue for screening, the medical assistant or staff receives a notification in PROMPT and offers to take a retinal photo during the visit. They may also send the member to the ophthalmology department for a same-day screening or schedule an appointment within 1 month.

These targeted outreach and inreach efforts are further guided by a risk calculator, or algorithm, which was developed by physician eye-care leaders in partnership with investigators at the KP Northern California Division of Research. The algorithm helps to predict the onset of retinal complications in people with diabetes. The Division of Research published a study about this algorithm, “Development and Validation of a Diabetic Retinopathy Risk Stratification Algorithm,” in Diabetes Care (a publication of the American Diabetes Association) in March this year. The study’s lead author is Dariusz Tarasewicz, MD, a former TPMG ophthalmologist who helped develop the TPMG Eye Care Monitoring program.

“The high volume of electronic health record data collected with patient permission at Kaiser Permanente can be used to help predict adverse outcomes before they occur,” says study co-author Andrew Karter, PhD, senior research scientist with the Division of Research. “Using computer models, we created a simple way to calculate risk of diabetic eye disease so that we can identify the higher-risk patients and prioritize them for earlier screening.”

The algorithm is based on more than 250,000 members with diabetes in KP Northern California between 2008 and 2020. It identifies nine readily available clinical variables — including taking insulin, blood sugar level, age, and blood pressure — to rank patients for the onset of diabetic eye disease. This has allowed the screening program to more efficiently prioritize and target outreach to at-risk patients with tailored strategies developed by TPMG Health Engagement Services, TPMG Consulting Services, and the Regional Outreach Strategy Center of Excellence (ROSCOE).

“This is how we leverage our research findings to apply them to care delivery,” Dr. Chen says. “We plug what we’ve learned from the risk calculator back into the outreach mechanism and apply it with more focus and intention to the people who are most likely to benefit.”

Increasing access and convenience

During the pandemic, TPMG’s ophthalmology, optometry, and quality departments continued to refine their design by making retinal cameras even more accessible. The team placed more than 60 retinal cameras in departments other than ophthalmology to make screening more convenient for patients, including 50 cameras located in AFM departments, staffed by medical assistants trained to use the cameras. This expansion began in 2017, and continues today.

As cameras become less expensive and more portable, the Diabetic Retinopathy Screening team leaders envision placing additional ones in more nontraditional settings like pharmacies and emergency departments. The goal is to increase screening rates to 85% across KP Northern California by 2025.

“Health screening programs like this one are ‘best-practice recipes’ that can be scaled and spread across the population that needs it,” says Dr. Chen. “Effective strategies revolve around something as simple as letting the patient know that they need the screening, and then designing ways to make that screening more convenient for patients to say ‘yes.’

“If I tell you you’re due for a breast cancer screening, and in that email there’s a link to click and make an appointment,” she continues, “then the response rate is higher. We’ve learned this from mammography and cervical cancer screening, and now we’re applying what we learned to other important screenings like this one that can mean the difference between blindness and sight.”

This article originally appeared in the Vol 8, No. 2, 2023 issue of Permanente Excellence magazine.