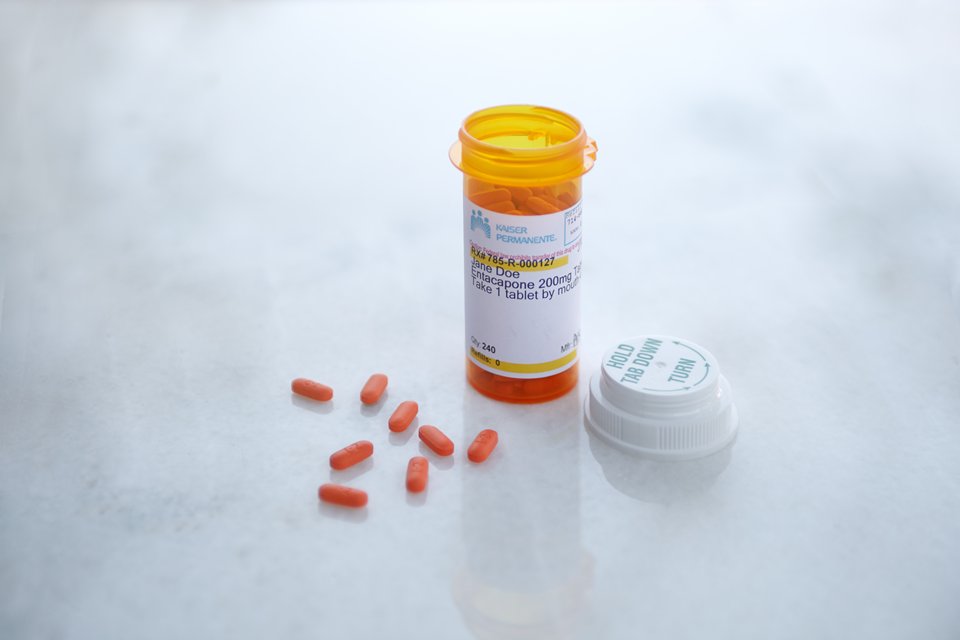

Demonstrating that taking a daily pill to prevent H.I.V. infection can work in the real world, San Francisco’s largest private health insurer announced Wednesday that not one of its 657 clients receiving the drug had become infected over a period of more than two years.

That outcome contradicted some critics’ predictions that so-called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, would lead to less condom use and more H.I.V. infections.

A study published in Clinical Infectious Diseases found that the San Franciscans on PrEP, almost all of whom were gay men, did use fewer condoms — and contracted several other venereal diseases as a result. But none got H.I.V.

Most other sexual infections, while potentially dangerous, can be cured with antibiotics. H.I.V. cannot, though it can be controlled with antiretroviral drugs taken for life.

“This is very reassuring data,” said Dr. Jonathan E. Volk, an epidemiologist for the insurer, Kaiser Permanente of San Francisco, and the study’s lead author. “It tells us that PrEP works even in a high-risk population.”

Observational studies like this one are not considered as scientifically rigorous as randomized clinical trials in which some participants receive a placebo.

But Dr. Volk and his colleagues followed a large number of men engaged in very risky behavior from mid-2012, when the Food and Drug Administration approved the use of a two-drug combination called Truvada for prevention of H.I.V. infection, through February of this year.

That amounts to 388 “person years” of observation.

By contrast, in a 2014 clinical trial among gay men in England, participants who received a placebo instead of Truvada had nine infections for every 100 person years of observation, said Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, the director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

That trial, nicknamed the Proud study, was one of several that were stopped early because researchers decided it was unethical to keep some participants on a placebo once it had become abundantly clear that PrEP worked.

“This shows that the effectiveness of PrEP is really strikingly high,” Dr. Fauci said. “And this study takes it out of the realm of clinical trials and into the real world.”

The newest study “fills in a critical gap by showing that PrEP can prevent infections in a real-world public health program,” said Mitchell J. Warren, the executive director of AVAC, an organization lobbying for AIDS prevention.

About a third of all San Franciscans with private health insurance use Kaiser Permanente, which has its own hospitals, doctors and pharmacies and tracks all of its patients in one electronic records system.

About a third of all San Franciscans on PrEP receive the drug through Kaiser, and its doctors urge all their clients who are at risk to ask if PrEP is right for them, Dr. Volk said.

All but four of the 657 participants in the Kaiser study were gay men, and 84 percent of them reported multiple sexual partners.

After starting PrEP, half of them became infected with syphilis, gonorrhea or chlamydia within a year.

After the participants had six months of PrEP use, Dr. Volk’s team surveyed 143 about their sexual behavior.

More than 40 percent said that their use of condoms had decreased.

The vast majority, 74 percent, said that their number of sexual partners had remained the same.

Previous studies have shown that PrEP is highly effective at preventing infection when participants take all or most of their daily pills.

The Kaiser study did not take blood samples to see whether its clients were taking the Truvada regularly, but all the men were on PrEP specifically because they had asked their primary care doctors for it and so presumably intended to take it, Dr. Volk said.

Although it is possible that PrEP contributed to higher rates of syphilis, gonorrhea and chlamydia, rates of those infections had begun climbing among gay men even before PrEP became available, Dr. Volk said.

The authors of the English study noted the same phenomenon.

The infections may have begun rising, Dr. Volk said, as some gay men began “sero-sorting” — choosing to have condomless sex only with men of the same H.I.V. status as themselves — or because H.I.V.-negative men agreed to have condomless sex with infected men who were taking their antiretroviral drugs so regularly that their blood levels of H.I.V. were undetectable, meaning they almost certainly could not pass that infection on.

“PrEP is another line of defense,” Dr. Volk said. “This is exciting news.”

This article was originally published in The New York Times on Sept. 2, 2015